What is Canadian cuisine?

While that recurring question can't simply be answered with poutine and maple syrup, those are definitely two little specks that help make our country's food scene as vibrant and unique as it continues to be.

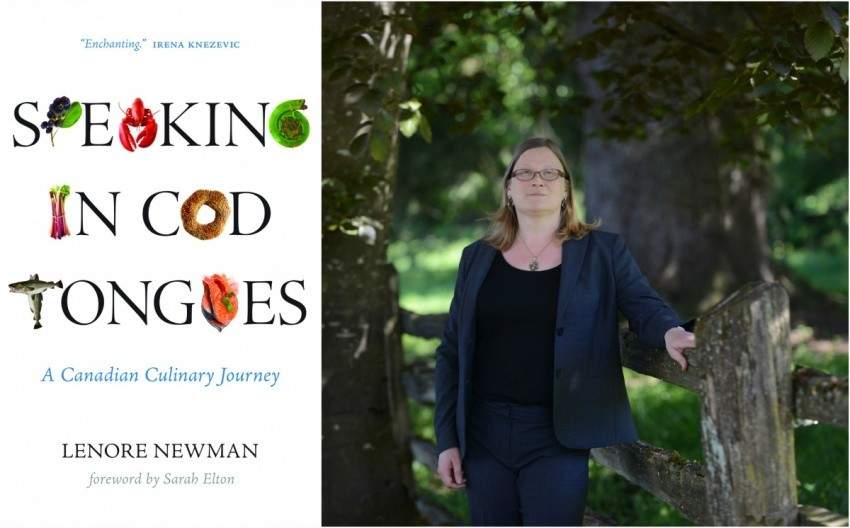

Dr. Lenore Newman is a Canadian who is especially interested in the food systems of our country. She is currently the director of University of The Fraser Valley's Agriurban Research Centre and holds a Canada Research Chair in food security and the environment. With her new book, Speaking in Cod Tongues: A Canadian Culinary Journey, Dr. Newman chronicles her extensive journey across the country, leaving no stone (or perhaps soil is a better analogy) unturned when it comes to how Canada's food identity has come to be.

From historical events that have resulted in our coast-to-coast multiculturalism to the Creole culture and how different international cuisines have fused together to become something unique altogether, the chapters of this book paint a picture of a Canada that we should all be very proud of. Written with academics in mind, Speaking in Cod Tongues is be no means an easy read, but certainly a valuable one, especially this year, seeing as it's the country's 150th birthday on July 1st.

Here, the author opens up about her preconceived notions of Canadian food, how environmental impacts can threaten certain iconic ingredients and more.

For Speaking in Cod Tongues, you travelled all across Canada, which is no simple feat. What was that like?

Oh, I travelled! About 40,000 kilometres worth and mostly by car! Ha, ha. I got to know the country really, really well and got to have some truly amazing experiences on the road. One of my main goals was to get out of the major cities. They obviously offer a lot in terms of their food scenes, but I wanted to see where a lot of the food came from. That was the motivation behind a lot of my more extreme travels.

So, would you simply define Canadian cuisine as being very regional?

Well, to a degree. A lot of the problem [with culinary identity] is that many people attack the idea of cuisine from looking at French food. It’s well known, high quality and it has a set of fundamental recipes. Even though it is also very regional, a lot of people don’t really realize that. I see Canadian cuisine as the “new” Nordic. No one would ever say that Icelandic and Finnish cuisine are the same; they are very different, but they have properties that unite them. What I found with Canada was that we definitely have regional cuisines, but there are properties that unite it and ingredients that do appear all across the country.

Did you have preconceived notions of particular areas of Canada? What surprised you?

Oh, definitely! I went to Newfoundland not really knowing what I would find. I didn’t expect amazing cuisine. What I found was amazing food, amazing chefs, wonderful people and also a people who are still deeply mourning the loss of the Atlantic cod. It was much more complex than I had expected. Also, by the time I finished going through Alberta, I realized that it had to be treated differently than the rest of the Prairies. It was very distinct. That was a newer view compared to a lot of previous works that have been done on Canadian cuisine.

Due to its geography with the mountains and whatnot?

More-so culturally. It is a mountainous place with much more herding [than Saskatchewan or Manitoba] but also because of the way the province has developed with the oil industry. They have a distinct provincial cuisine that is notably different from the other Prairie provinces.

Multiculturalism is a huge part of our country's identity. Did you discover international foods while travelling that you didn't expect?

There were a couple of them that surprised me. In Montreal, I was surprised at the presence of Lebanese food and how ubiquitous it is. On a more rural note, I had never heard of the huge Icelandic population that exists in Manitoba. It’s very concentrated and they still stay true to their country's cuisine. My family is of Finnish descent, so I knew that Thunder Bay was full of Fins, but to go there, see it and hear that language spoken in a restaurant setting was kind of amazing!

Richmond, B.C. is a city that is primarily Chinese in population. Would you consider that city's food scene to be Canadian-Chinese or more of an actual transplant?

The word I use is Creole [in regards to blending of food cultures]. Canada develops Creoles. In much of the Pacific Rim, you will see this. Groups of people live together so long that they evolve a cuisine that reflects both groups. In Richmond, you can get those authentic regional cuisines from the provinces of China, so it is a little different, but even there, you see some of that blending. Certainly heading into Vancouver, you see blending with sushi. The Creolization, the use of local ingredients used in traditional techniques, it’s a very Canadian approach and it doesn’t translate to everywhere. In the United States, you certainly don’t see this as much except maybe in New Orleans with their French influence. If you were to present Vancouver sushi in Seattle, the critique you may get is, “Oh, that’s not right.”

Our country is viewed globally as being a very accepting country in terms of immigration. Is that the reason why our food scene is so unique?

It’s one of the big three. The big thing that defines Canadian cuisine is that multicultural approach. The second is seasonality. We really are connected to the seasons since we’re quite a ways away from the equator and we see those strong, four seasons. Thirdly, it would be our wild food. We eat much more wild game and foraged foods than most other places in the world.

Your book is fairly academic and cites many Canadian-authored works, like Anita Stewart's for example. Are these colleagues and friends or did you really delve deep into Canadian culinary literature?

A lot of these people I did talk to. I have never actually met Anita Stewart, but I [feel like] I am very much following in her footsteps because she broke so much ground on Canadian cuisine. This book is building on that work. This book is also a hybrid. It’s supposed to be an academic book that applies to the average person as well. I did that on purpose and some people say I’ve done that well and some people aren’t as thrilled (see Corey Mintz' full-length The Globe and Mail review here). Ha, ha...I really didn’t want this work to just end up sitting on a shelf for academics, I wanted everyone to be able to read that. It’s an experiment that hopefully worked!

You also touch on the future of food and how things like global warming threaten iconic Canadian ingredients. It's a scary, but very real thought.

It worries me. My work is now taking a turn to look at “endangered” foods and how global change and spreading of humanity are impacting our food systems. I think especially with an administration in the United States that’s not as, hm, focused on climate change —that’s about the most polite way I can put that I think— as we are, it’s very likely we could see some disruption to food systems. I worry about most, being a fisherman’s daughter, is what if the same thing happens to salmon like it did to cod on the East Coast? I hope I never live to see that happen, but it is a worry.

Can you think of a country that's currently in peril of losing a beloved ingredient?

You can look at Japan and see them struggle with the blue fin tuna. Ninety seven per cent of their bluefin tuna are gone and now they’re asking the question, “Should we really be eating these last few?” That’s where they’re at. It’s such a highly desirable food, though, that there’s huge pressure to fish [what’s left] and we’re seeing things like that happen around the world. Demand is beating out supply when it comes to certain foods.

What are a few homegrown ingredients that are due for some time in the limelight over the next few years?

There are a number that I think are waiting in the wings. We sort of have to wait and see what they do. I’m very found of the haskap berry. The haskap is native to Northern Canada, but the University of Saskatchewan are helping develop them to grow further south. They have potential. Arctic char is also a wonderful, wonderful fish and you see it on more and more menus these days. I also think that with changes to strict regulations nationally, we’re seeing a wonderful distilling industry appearing. That’s going to continue to grow because we have really, really clean water, which is essential to distilling and also to all of the grain that is required as a base.

Perhaps even the humble blackberry out here on the West Coast. I feel like it’s never really had its moment to shine!