Food. It provides the calories and nutrients we need to survive, but it also extends far beyond pure sustenance. Food is social, cultural, and pleasurable; that is to say, few things are as inextricably connected to the human condition as food. In the case of food addiction, however, the simple fact that food is required for survival may pose one of the biggest challenges. Unlike other addictions, there is no option to go “cold turkey”, short of researchers developing a pill that provides all of our nutritional requirements. We need to eat, more or less three balanced meals per day, lest we starve and die.

This is made all the more challenging by the fact that we encounter food-related stimuli pretty much everywhere we turn: food in our fridges, advertisements for food on TV, and of course, there’s the ever-important social media platform, Instagram, which most of the time, seems to be at least 90 per cent dedicated to insanely delicious looking food. Food, whether in person or through other 2-D channels, is unavoidable. And that’s where attentional bias research comes in.

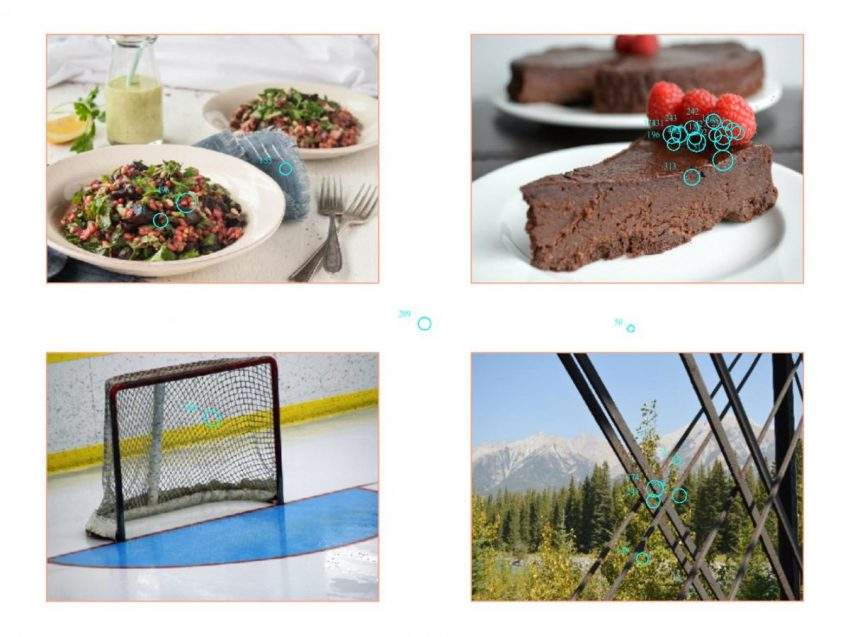

Attentional bias is exactly what the name sounds like, having biased attention towards particular stimuli. In this case, we’re talking about attentional bias towards food, and the implications this has for individuals with various forms of disordered eating, such as food addiction. Recent research from the University of Calgary (as a caveat, this was research I was fortunate enough to be involved in) decided to examine attention to food images in those with food addiction. Through the use of eye tracking technology (basically a fancy camera that tracks your pupil and is able to gauge what you look at and for how long), we were able to study how attention to food differed between those with and without food addiction, under both neutral and sad mood conditions.

First, we brought people into the lab who self-identify as having food addiction, as measured by the Yale Food Addiction Scale, the most common measure of food addiction. Then, we asked them to watch a neutral, non-emotional video and rate their mood to ensure it was neither positive nor negative. After calibrating the eye tracker to their pupils, we asked them to sit in front of a computer screen and look at 25 collages of images, each containing one healthy food image, one unhealthy food image, and two nonfood images, while the camera tracked and recorded what they looked at. Next, we asked them to watch another video, this time a sad one, and they rated their mood again to ensure it was now negative (this process is known as a mood induction, as we artificially induced a sad mood). Finally, they viewed another set of 25 images like before, but with different images.

Not surprisingly, being in a sad mood altered people’s attention to the images of food. However, the results might not be exactly what you would expect. For people with food addiction, their attention to healthy food images decreased while their attention to unhealthy food images increased following the sad mood induction. On the other hand, for people without food addiction, neither their attention to healthy or unhealthy food images changed following the sad mood induction–it had no effect. This is somewhat surprising, given that many people who don’t have “food addiction” per se still exhibit emotional eating tendencies, and therefore you would assume that they would also be susceptible to increasing their attention to food when in a sad mood.

This is all fine and dandy, as some would say, but the question becomes, “What are the real world implications of such findings?” I will be the first to admit that just because people look at food images more in a study like this doesn’t necessarily mean that it can be generalized and applicable to the real world, to real food, under naturally-elicited mood states, outside of an artificial lab setting. Yes, more research is needed to see if sad moods actually lead to increased food consumption, and yes, it is important to do this under conditions that are as natural as possible. Still, you cannot ignore the implications for findings of attentional bias in certain individuals, such as those with food addiction.

If we encounter food multiple times in a single day, what does this mean for those whose attention is compulsively drawn towards it? Going back to the Instagram example, what if looking at pictures of food isn’t just a mindless thing you do when you’re waiting for someone to meet you for coffee? What if it actually instigates overeating and subsequent weight gain? Given the prevalence of exposure to food via various social media channels, it would be extremely interesting to study the impact of this on actual eating habits (especially if you’re having a bad day and checking out Instagram to cheer yourself up). But short of following someone around with a camera attached to their head, it’s difficult to say whether attention to food images actually translates into attention to real food, and subsequently eating and over-consuming that food.

If you want to read the full article by Frayn, Sears, & von Ranson (2016, in press), check it out here: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0195666316300435