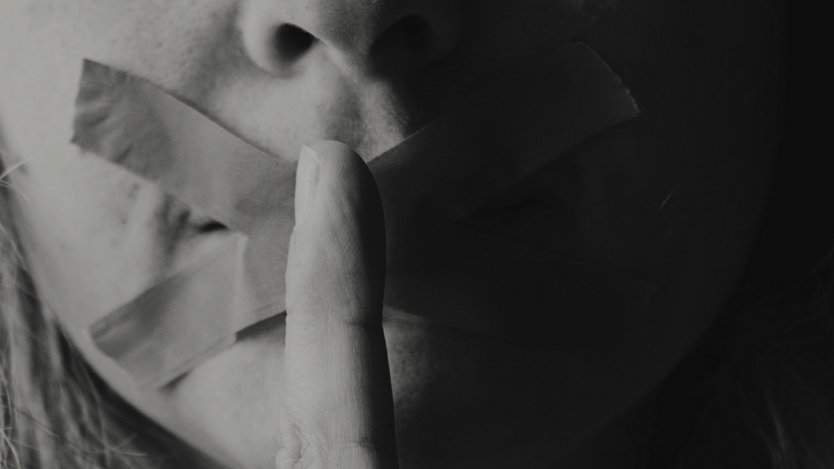

From accusations against big name chefs, like Mario Batali and John Besh, to the recent Globe and Mail investigation on Norman Hardie, discussions about sexual harassment in the culinary industry are at an all-time high, and rightfully so. However, despite more victims speaking out and more chefs and restaurateurs denouncing the behaviour of their peers, there’s still a lot of silence when it comes to a topic that is in dire need of attention.

Outspoken restaurateurs like Toronto’s Jen Agg and Montreal’s David McMillan have even gone as far as to call out their peers for their inaction towards the issue. Agg took to Twitter shortly after the Hardie story was published, stating, “Prominent friends and supporters of Norm who still haven’t spoken up (as far as I can tell) you HAVE to say something. People can see you not saying anything.”

She went on to say, “You can’t just pretend this isn’t happening. By not publicly condemning Norm’s actions you’re saying ‘It’s ok that he harassed women, I’ve never seen it and he’s a nice guy and I really like his wine’. You’re really saying you just don’t care about women.”

So why do people seem to have such a difficult time breaking the silence?

To be clear, none of what is described below aims to excuse or justify inaction. Rather, it aims to examine the social constructs that may help to explain some of it; it’s not a one-size-fits-all explanation to encompass all situations.

Humans are inherently social creatures, but group interactions can often be subtle; even without overt, malicious intentions, they can still go down the wrong path.

Groups can facilitate a sense of deindividuation, or the reduced sense of self and lower self-regulation that comes with being part of a large body of people. Rather than exerting our own ideals and values, we tend to blend into the group we are part of. In the restaurant industry, where a misogynistic culture has long been the norm, even those who personally disagree with the values being endorsed may feel like they have no choice but to go along with them. In fact, they may not even consciously realize that they’re going along with them at all.

Zajonc’s model of social facilitation aims to explain how the presence of other people can facilitate performance. It states that on well-learned, simple tasks, the presence of others can elicit a dominant response and thus facilitate performance. Based on this theory, in a kitchen context, a simple task like cutting onions would be facilitated by having others around. However, the model conversely states that on more difficult, novel tasks, performance is decreased, because the response needed is not the dominant or automatic one. In kitchen culture, speaking out against the wrongs experienced is not the dominant response, rather, staying silent is. It’s an interesting paradox, but based on the model of social facilitation, public pressure to speak out on these issues may in fact be reducing the likelihood that this actually happens.

The silence from people in power may also be attributed to social loafing, which is the tendency to exert less effort in a group context where you know that your individual contribution cannot, or is not, going to be assessed and accounted for. While this may not be true, there is no formal system in the restaurant industry for keeping people accountable. So when a small number of people are doing most of the talking, it’s easy for other individuals to take the backseat and assume that their contribution won’t make a difference.

When victims themselves do have the courage to speak out, the response they get is unfortunately often not in line with what they expect. We can look to the bystander effect for a better understanding of why this may be the case. The famous case of Kitty Genovese, which is described in virtually all intro and social psychology textbooks, is regularly used to explain this construct. Back in the ‘60s, Kitty was walking home to her apartment when she was stabbed and killed. Over the course of the ordeal, it is estimated that almost 40 witnesses heard her screams, yet none intervened. The explanation for this is that in such situations, there is often a diffusion of responsibility. In other words, people are not particularly inclined to help out because they assume that someone else will step up to bat.

The take away from many of these explanations is not exactly optimistic, and tends to draw a fairly dire picture of the nature of human interactions in groups, in the culinary industry or otherwise. So, how do we encourage people to speak up?

Given that groups can have the negative influence of promoting deindividuation, the opposite response to this is to try and encourage individuation. Focusing inward on the self can lead people to be more aware of and thus act in accordance with their morals and values. Similarly, self-awareness theory aims to facilitate individuation by having people focus attention inward on themselves. This then leads to self-evaluation to reflect on whether or not their current behaviour is consistent with their core values. Studies testing this theory have shown that something as simple as putting people in front of a mirror makes them less likely to cheat on a test or task.

Applying individuation to kitchen culture can happen on all levels, but seems like it would be most effective if those in positions of power engage in this self-reflection to determine the extent to which their actions align with their values. If they change their behaviour in a positive way, they can act as leaders for others to follow suit.

On a peer-to-peer level, if we go back to bystander intervention, we know that people are more likely to intervene when they perceive the victim to be similar to themselves. The good news about this is that more and more victims are speaking out, and their stories are resonating with those who have endured similar experiences.

Groups can be great things; after all, there is power in numbers. They key is that the norms they are promoting encourage respect and equity for all involved.