Canada is the home of pioneers.

The light bulb, insulin, basketball and five-pin bowling — just a few of our greatest contributions to humankind. No big deal.

So, as craft brewing is quickly reaching its cultural zenith, Canada is again at the forefront with our take on Japanese sake.

We can boast the presence of three sake microbreweries: Artisan Sake Maker, YK3 Sake Producer and Ontario Spring Water Sake Company— an amazing feat for a country with such a relatively small population. Our neighbours to the South have several large commercial sake breweries based mainly in California, but their craft scene has been scant at best. In 2008, moto-i in Minneapolis was established. [Full disclosure: I was moto-i’s sake educator and assistant brewer.] moto-i was the first sake brew pub outside of Japan with a modest output of namazake (unpasteurized sake) served on tap for its patrons only. Since then, there’s been an emerging influx of new American microbreweries in Texas, Maine, Washington State and North Carolina — all in their infancy, and at this point, not a lot of output. But the shift is happening and sake will finally see its day in the spotlight. I’m convinced a craft sake explosion will occur in the next few years, where we’ll see many more small commercial brews offered across North America.

What’s Canada’s contribution to this scene?

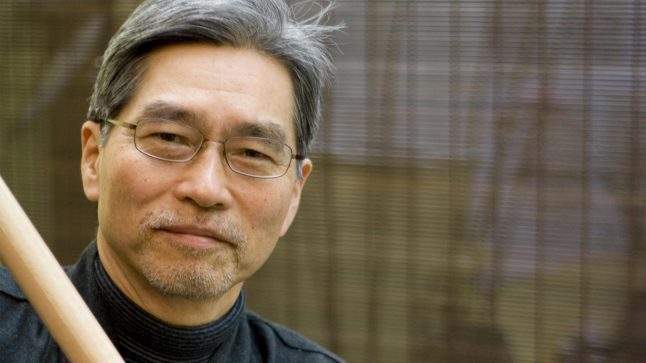

In 2007, Artisan Sake Maker became the first North American commercial sake microbrewery to open its doors in the busy Granville Island market district in Vancouver, B.C. Masa Shiroki, a former provincial public servant who turned to sake importing before embarking on its production side, sees himself as a reluctant pioneer. Lamenting on the dearth of premium sake selection in B.C., Shiroki began importing from Japan in 2001 and saw the venture as more of a necessity. Six years later, he decided to try his hand at brewing, with the help of a consultant from Japan.

Shiroki believes that the desolate craft sake trinity in Canada exists for many reasons. Our continued lack of selection,high import costs and provincial liquor taxes that further raise sake’s price point all prevent consumers from finding affordable sake options, thereby muzzling their interest in exploring sake at all, and leaving importers with low profitability and no reason to bring in more product.

“We’re only one-tenth of the population compared to the U.S., so the market is very small and in order for you to be able to run a viable business to import and distribute sake, and to have enough money to hire someone to sell — it’s hard. And it was very hard for me from the very beginning, so I stopped and thought: ‘Is this the model that I really want to go forward with?’”

What spurred Shiroki to start a sake brewery in Vancouver was the need to counter the public’s detachment to sake. “With imported sake, people will say, ‘Oh it’s an import. It’s their sake’. So I began to ask myself, ‘If I made sake here, how would that be perceived? Would people take more ownership of it, meaning that this is our sake?’”

The experiment paid off. Shiroki’s Granville Island Osake line has been embraced by the many local and foreign visitors who pop into his loft space for a tastings. All Granville Island Osake products are namazake, which means they are unpasteurized. Most sakes, unless otherwise indicated, will go through double pasteurization: once before being laid down for about six months to settle and then once more, after bottling.

Having a lively, zingy nama is a treat, and typically, you can only enjoy this in the springtime in Japan, which is when new sake brewed in the fall is ready to consume. Costs to import namazake are extremely prohibitive as the sake requires constant cold storage.

Visitors to Shiroki’s studio have an opportunity to taste what unpasteurized sake is like. Currently, there are no Canadian sake importers bringing in seasonal namazake, but they are available in larger U.S. cities.

Shiroki’s sakes can also be found at various B.C. private liquor stores and restaurants in B.C. and Alberta. Recently, he started to keg his sakes for draft dispensing. PiDGin Restaurant in Gastown and the Fairmont Pacific Rim’s Oru Restaurant are the first to offer Granville Island Osake on tap. The kura, or brewery, also sells secondary sake products like salad dressings, juice, ice cream, chocolates and cosmetics made from kasu, the lees that remain after pressing sake. In Japan, nothing gets wasted in the sake-making process and Shiroki’s kura is true to that philosophy.

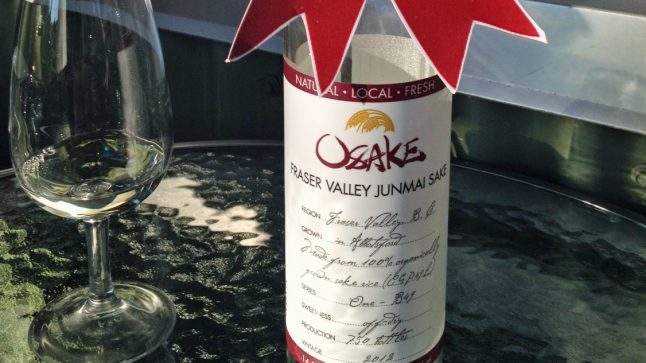

A perennial workaholic, Shiroki is not one to rest on his laurels for his many sake ‘firsts’ in Canada. In fact, his latest venture has him out onto the verdant fields of agriculture. Last year, he successfully planted and harvested one ton of sake rice on two acres of farmland in B.C.’s Fraser Valley. Using his locally grown rice, he claims to have made the first true Canadian sake, made from 100% Canadian raw materials. The limited-run Granville Island Osake Fraser Valley Junmai Sake is still available at Shiroki’s kura, and response has been so positive that he anticipates it will sell out in a matter of weeks.

Shiroki’s sake rice (or sakamai, as it’s called in Japan) is a form of Ginpu — hardy sake rice that is largely grown in the Hokkaido region of Northern Japan — that has a distinctly Canadian name due to its local planting and cultivation in B.C. Not a very sexy name, CGP49L, as it’s technically called, stands for Canadian Ginpu 49 Degrees Latitude.

Shiroki hopes to one day cultivate enough sake rice to provide him with the B.C. designation of land-based winery, which would exempt him from paying the painfully hefty 123% liquor tax markup that designated, commercial wineries, are charged. Shiroki explains he is currently licensed as a commercial winery, which he says, “really really sucks, bottom-line-wise.”

To qualify as a land-based B.C. winery, manufacturers are required to own or lease a minimum of two acres of land in which fruit or grain is grown specifically for winery production, and at least 25% of that earmarked harvest must derive from the winery’s owned or leased land. You can source the rest of your raw materials elsewhere, but they must be 100% B.C. grown.

Opening the door to the idea of paying zero markup tax obviously excites the bureaucratically whip-smart Shiroki, but there’s a lot more work to be done and he’s not convinced that he’s farmer material.

“You have to be able to supply [source] all your ingredients within B.C. which means, do I become the farmer or the producer of the rice for the sake we are going to make in the future? Because we’ll have to expand then, and I…I just don’t think so. I’d rather have contractual arrangements with the farmers who’d be interested in doing it for us.”

Locality has obvious, great consumer appeal and there are certainly advantages for Shiroki to continue pushing forward with making his brews as distinctly regional as possible. From importer to brewer to farmer, Shiroki is tireless in his efforts to refine and redefine what sake means to him. When I ask him about Canada and what makes us a hotbed for craft sake making compared to the States, Shiroki smiles and wryly philosophizes, “We are very unique in the sense that none of the three Canadian sake makers came from beer making backgrounds. That’s unique. Maybe we’ve set a precedence that has made people think, ‘Oh, look at them. It shouldn’t be that difficult to do!’”

Check back for the second and third installment of our three-part sake triptych on Canada’s craft sake breweries: YK3 Sake Producer from Richmond, BC, and Ontario Spring Water Sake Company of Toronto.