Love in the workplace is usually frowned upon, but every now and then, cupid has his way. When Dyan Solomon and Eric Girard opened Olive et Gourmando--now a Montreal staple--21 years ago, little did they know that their own love story would set the stage for that of their employees. Several of the couples who met at Olive and Gourmando years ago are still together, and many of them even have kids.

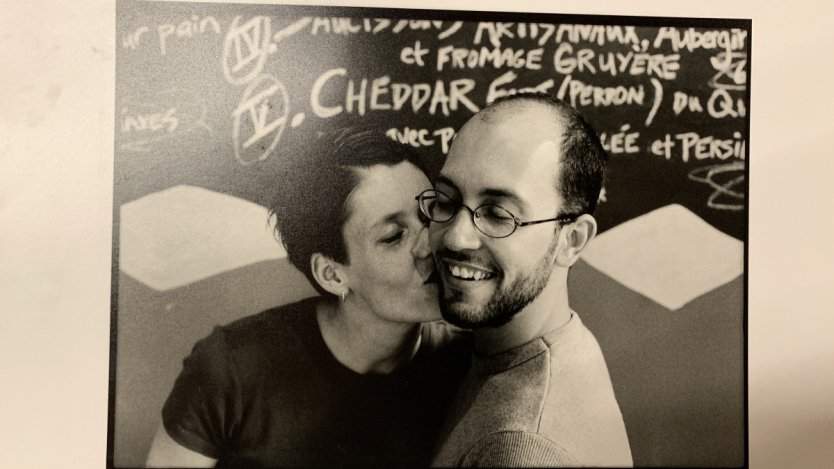

Solomon and Girard themselves met at one of Montreal’s best, Toqué. Girard was a cook turned baker, Solomon was a cook come pastry chef, and perhaps with all of the sweetness that their jobs entailed, there was no other option but for a relationship to form between the two. Even today, although the couple is now separated, they remain business partners with a growing group of restaurants that includes Foxy, Un Po’ Di Più, the recently opened Olive et Gourmando stall in the Time Out Market, and a new bakery that is slated to open in spring 2020.

“I don’t want to have any other business partner. She’s too much a part of my life; she’s still my Valentine,” Girard jokes.

Despite having opened their first business as a couple, it wasn’t until later reflection that Solomon realized the effect that had on the environment in which she worked. “I think it started with us. Although it wasn’t something we encouraged, we were a couple that was loving, affectionate, and had a lot of fun. I think we infected people with that,” she reflects. Infected they did. At one point, Solomon describes working with a team comprised of four sets of couples, all of whom had met in the workplace.

Girard seconds Solomon’s sentiment, adding that their openness and willingness to communicate about their situation also played a role, even when they separated, romantically. “We were very careful when we split and I think they [the staff] really appreciated that,” he says. “There was a lot of trust; they always talked with us.”

While it may be easy to think of all the ways in which relationships in the workplace could go wrong and detract from the work environment in the process, Solomon describes an organicity to what she observed. With her and Girard leading by example, she believes that the couples that rose from this ultimately played a significant role in maintaining a positive atmosphere.

“There’s a beautiful element to it as well when two people fall in love under your roof. You feel like you’ve contributed to the environment that facilitated this matchmaking; it’s very satisfying,” Solomon says. “Both of these people work for you, are dedicated to the company, fall in love, and become more dedicated in a way, committed to each other and the place they fell in love.”

Although conflict is a big concern in relation to couples, she goes on to add that this was never an issue that she observed. “We’ve been extremely lucky working with couples who are professional and able to keep that outside the workspace,” she admits. “They have seemed to be at a very happy time in their life.”

As for the downsides to workplace romances, Solomon admits that she didn’t start to notice these until her own relationship dissolved. With a growing empire of restaurants, the pair find themselves more involved in the operational aspects of running their businesses and less so in the trenches of their restaurants.

“I never made these connections until 21 years later,” she laughs. “We were very much in charge of setting the tone at Olive. Now, we have teams of management people. We are one group removed and it has changed that dynamic.”

In terms of what this change has looked like, Solomon says, “If there are issues with one, we are afraid that they both might leave together,” she says. She adds that even if there aren’t “issues” per se, if one member of a couple decides to quit, the likelihood of the other following suit is high. “You lose an employee that you wouldn’t have lost otherwise,” she says.

And it’s not only the prospect of losing staff that can lead to issues. Girard points out purely logistical concerns regarding time off when there is not one person, but two people, involved. “When they take a vacation or decide to do something, you are without two key members of your team,” he elaborates.

Having transitioned from romantic and business partners, to solely business partners, over the course of decades in the industry, Solomon says that they are still flushing out their exact policy with regards to workplace relationships. “We will definitely have to come up with some kind of rules and regulations to make it easy to terminate [staff] if we get to a crisis moment,” she admits.

But both her and Girard are unanimous in their thinking about what it takes to make workplace relationships work in the restaurant industry, emphasizing both communication and leading by example.

“You have to be real, to be open, and to listen. A lot of people don’t listen,” Girard says. And importantly, Solomon adds, “It starts at the top. I can’t emphasize enough how true that is.”